The physicist and author of A Brief History of Time has died at his home in Cambridge. His children said: We will miss him for ever

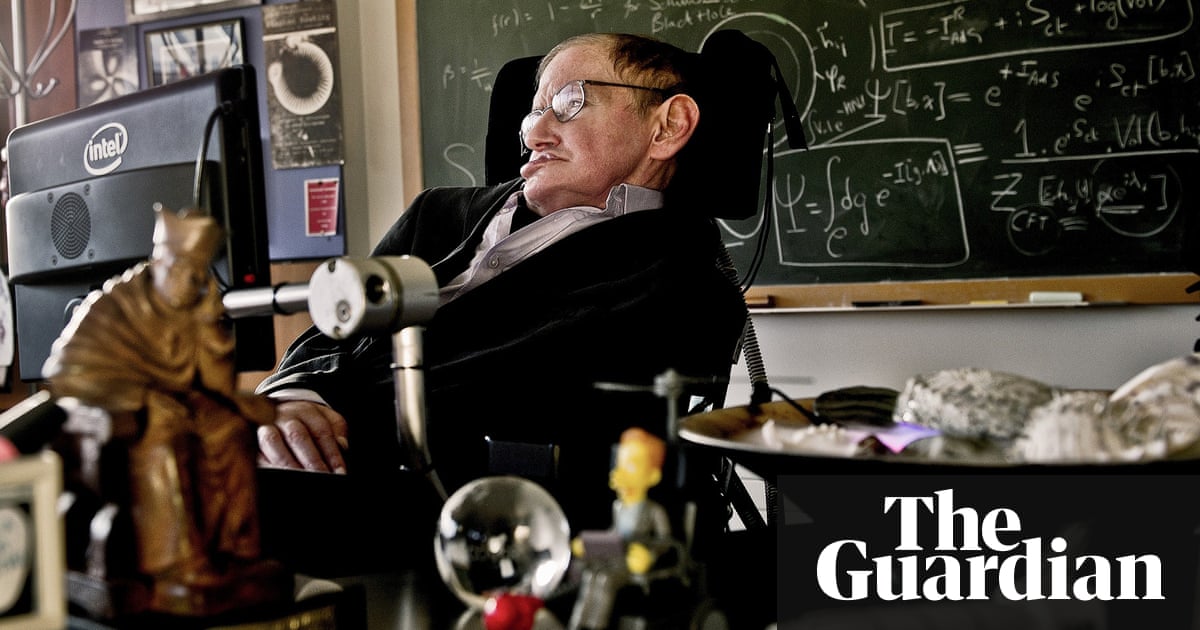

Tributes poured in on Wednesday to Stephen Hawking, the brightest star in the firmament of science, whose insights shaped modern cosmology and inspired global audiences in the millions. He died at the age of 76 in the early hours of Wednesday morning.

In a statement that confirmed his death at home in Cambridge, Hawkings children said: We are deeply saddened that our beloved father passed away today. He was a great scientist and an extraordinary man whose work and legacy will live on for many years. His courage and persistence with his brilliance and humour inspired people across the world.

He once said: It would not be much of a universe if it wasnt home to the people you love. We will miss him for ever.

For fellow scientists and loved ones, it was Hawkings intuition and wicked sense of humour that marked him out as much as the fierce intellect that, coupled with his illness, came to symbolise the unbounded possibilities of the human mind.

Stephen was far from being the archetypal unworldy or nerdish scientist. His personality remained amazingly unwarped by his frustrations, said Lord Rees, the astronomer royal, who praised Hawkings half century of work as an inspiring crescendo of achievement. He added: Few, if any, of Einsteins successors have done more to deepen our insights into gravity, space and time.

The Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield lamented on Twitter that Genius is so fine and rare, while Theresa May noted Hawkings courage, humour and determination to get the most from life was an inspiration. The US rock band Foo Fighters was more succinct, calling Hawking a fucking legend.

Hawking was driven to Wagner, but not the bottle, when he was diagnosed with motor neurone disease in 1963 at the age of 21. Doctors expected him to live for only two more years. But Hawking had a form of the disease that progressed more slowly than usual. He survived for more than half a century.

Hawking once estimated he worked only 1,000 hours during his three undergraduate years at Oxford. In his finals, he came borderline between a first- and second-class degree. Convinced that he was seen as a difficult student, he told his viva examiners that if they gave him a first he would move to Cambridge to pursue his PhD. Award a second and he threatened to stay. They opted for a first.

Those who live in the shadow of death are often those who live most. For Hawking, the early diagnosis of his terminal disease, and witnessing the death from leukaemia of a boy he knew in hospital, ignited a fresh sense of purpose. Although there was a cloud hanging over my future, I found, to my surprise, that I was enjoying life in the present more than before. I began to make progress with my research, he once said. Embarking on his career in earnest, he declared: My goal is simple. It is a complete understanding of the universe, why it is as it is and why it exists at all.

He began to use crutches in the 1960s, but long fought the use of a wheelchair. When he finally relented, he became notorious for his wild driving along the streets of Cambridge, not to mention the intentional running over of students toes and the occasional spin on the dance floor at college parties.

Hawkings first major breakthrough came in 1970, when he and Roger Penrose applied the mathematics of black holes to the universe and showed that a singularity, a region of infinite curvature in spacetime, lay in our distant past: the point from which came the big bang.

Penrose found he was able to talk with Hawking even as the latters speech failed. Hawking, he said, had an absolute determination not to let anything get in his way. He thought he didnt have long to live, and he really wanted to get as much as he could done at that time.

In 1974 Hawking drew on quantum theory to declare that black holes should emit heat and eventually pop out of existence. For normal-sized black holes, the process is extremely slow, but miniature black holes would release heat at a spectacular rate, eventually exploding with the energy of a million one-megaton hydrogen bombs.

His proposal that black holes radiate heat stirred up one of the most passionate debates in modern cosmology. Hawking argued that if a black hole could evaporate, all the information that fell inside over its lifetime would be lost forever. It contradicted one of the most basic laws of quantum mechanics, and plenty of physicists disagreed. Hawking came round to believing the more common, if no less baffling, explanation that information is stored at a black holes event horizon, and encoded back into radiation as the black hole radiates.

Marika Taylor, a former student of Hawkings and now professor of theoretical physics at Southampton University, remembers how Hawking announced his U-turn on the information paradox to his students. He was discussing their work with them in the pub when Taylor noticed he was turning his speech synthesiser up to the max. Im coming out! he bellowed. The whole pub turned around and looked at the group before Hawking turned the volume down and clarified the statement: Im coming out and admitting that maybe information loss doesnt occur. He had, Taylor said, a wicked sense of humour.

Hawkings run of radical discoveries led to his election in 1974 to the Royal Society at the young age of 32. Five years later, he became the Lucasian professor of mathematics at Cambridge, arguably Britains most distinguished chair, and a post formerly held by Isaac Newton, Charles Babbage and Paul Dirac, one of the founding fathers of quantum mechanics.

Hawkings seminal contributions continued through the 1980s. The theory of cosmic inflation holds that the fledgling universe went through a period of terrific expansion. In 1982, Hawking was among the first to show how quantum fluctuations tiny variations in the distribution of matter might give rise through inflation to the spread of galaxies in the universe. In these tiny ripples lay the seeds of stars, planets and life as we know it. It is one of the most beautiful ideas in the history of science, said Max Tegmark, a physics professor at MIT.

But it was A Brief History of Time that rocketed Hawking to stardom. Published for the first time in 1988, the title made the Guinness Book of Records after it stayed on the Sunday Times bestsellers list for an unprecedented 237 weeks. It sold 10m copies and was translated into 40 different languages. Some credit must go to Hawkings editor at Bantam, Peter Guzzardi, who took the original title: From the Big Bang to Black Holes: A Short History of Time, turned it around, and changed the Short to Brief. Nevertheless, wags called it the greatest unread book in history.

Read more: http://www.theguardian.com/us