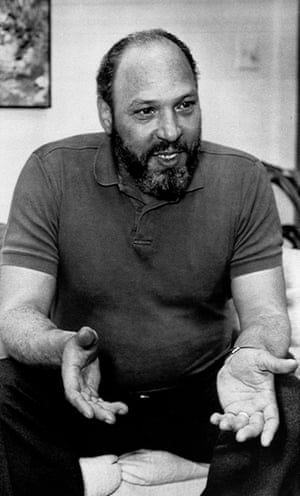

The playwright captured an entire century of black American experience. His widow Constanza Romero explains how she shares his message, as gritty play King Hedley II returns to the stage

It is one of his most difficult plays, says Constanza Romero. Its very gritty death runs all through it. Romero, the widow of August Wilson, is talking about King Hedley II, his drama about a young man trying to rebuild his life after a stretch in prison, having returned to his childhood home in a dilapidated area of 1980s Pittsburgh.

King Hedley II, which has just opened at Londons Theatre Royal Stratford East, is the penultimate instalment of an epic 10-play series Wilson wrote over the course of about 25 years, each representing a different decade of the 20th century and each focusing on the lives of African Americans. The play was first produced in 1999, and opened on Broadway two years later. Wilson died from liver cancer four years after that.

I knew somebody had to be the decision-maker for what was to come, says Romero of the work her late husband left. I asked August a few things about how he would handle this, how he would handle that. He had made a very courageous peace with the fact that he was going to die. From that courage, I basically said, Ive got to be the caretaker of this incredible legacy. Ive never really thought about it as a decision. I think of it as a gift.

Two of these 10 plays won the Pulitzer prize for drama: Fences in 1987 and The Piano Lesson in 1990. The series is commonly referred to as the Pittsburgh Cycle because all but one is set in the Hill District of the city where Wilson grew up. Romero, however, is quick to correct this. The actual title is the American Century Cycle. There is this other title floating around. Part of my goal as executor of the estate is to inform people that there is only one. Where did the other title come from? Romero laughs: People in Pittsburgh! Hes Pittsburghs native son.

Wilson was born Frederick August Kittel Jr in 1945 to a German immigrant father and an African American mother. His father, a baker, was rarely around, and his mother raised her six children and later remarried. Adopting her surname as a young man, Wilson wrote poems and did odd jobs before achieving success as a playwright.

The American Century Cycle, Romero says, was born from Wilsons love of the past. He was always interested in history, she says, speaking from her home in Seattle. By the time he wrote Joe Turners Come and Gone, the cycles second play, he basically said, Hey, Im writing about different decades in the 20th century. Why dont I continue? I think it gave him a structure he could work within. He tried to have all 10 cut from the same cloth. Thats how he described it.

However, before he passed away, he was working on another play he was really excited to finally be liberated from that structure. He was going to make that play totally different from the rest. He even had the idea for a novel in his back pocket.

As his literary executor, Romeros days are varied and busy. She approves requests to stage Wilsons work, travels to watch productions, and is currently working on a Spanish translation of Joe Turners Come and Gone. An acclaimed costume designer, she also does projects outside of Wilsons writing to keep my hands in textiles. This year, Romero will work on an adaptation of Joan Didions of The Year of Magical Thinking in Seattle.

However, she says, most of my working day is taken up with August Wilson. I always say, Its a well that never runs dry. As if to prove the point, later this year Nancy Medina will direct Two Trains Running, the cycles 1960s play, for English Touring Theatre.

Romero was born in Colombia to a Colombian father and American mother, and moved to the US when she was 11. She and Wilson met while she was a third-year student at the Yale School of Drama, when she was assigned with designing the costumes for The Piano Lesson. There was immediate connection as artists, but our friendship grew from there. That was in 1987. In 1991, we both moved to Seattle. They had a daughter, Azula, and continued to collaborate on plays, the three travelling together. Romeros costume designs for Gem of the Ocean and Fences were nominated for Tony awards.

He would be sitting by my drawing table, she says, and I would be sketching one of the characters that he was starting on before he had finished his draft. A couple of times, he saw my sketches, and he looked at them really closely and he would say, Huh, Im going to go downstairs and write the character to fit more like the sketch.

When Wilson died in 2005, his country was on the cusp of having its first African American president. What would Wilson have made of Obama and of the later election of a billionaire reality TV star? Oh my gosh, I just cant imagine, says Romero. His heart was really big. Most of the time, especially in his writing, he exposed that heart so beautifully. I cant imagine what the condition of that heart would be had he lived through the Trump presidency.

Still, she says, Wilsons work keeps her optimistic. Its not just his plays: its the art of theatre itself. I am in awe of how potent an instrument it is. Those stories being told, the amount of humanity, the commonality that he finds in all his characters, the universality all of that gives me hope.

For Romero, working so closely with her late husbands work hasnt always been easy. Its almost been 15 years since he died. Going from a place of loss and thinking, gee, hes in the next room. Or at least making myself think hes in the next room, so if I go there, hell be there, and hes not. But straight after [his death] , we had anAugust Wilson series in New York City. Sitting in the audience for those three plays, I remembered so many private jokes that we had, things that other people probably dont find funny. So I said, oh my gosh, his voice lives on. Hes still making me laugh. He still makes me cry.

- King Hedley II is at Theatre Royal Stratford East, London, until 15 June.

Read more: http://www.theguardian.com/us